Insecurity

Insecurity, or lack of safety, is a source of fear and anxiety that negatively affects wellbeing. To devise approaches to its measurement, Stiglitz et al (2009) distinguish between personal and economic insecurity. Personal insecurity includes external factors that put at risk people’s physical integrity, such as crimes and accidents. Economic insecurity covers uncertainty about the material conditions that may prevail in the future. For instance, uncertain income or out-pocket-medical expenses may generate stress and anxiety and make it harder for families to spend on other expenditures such as housing or education. The social right to economic security is United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights is generally enforced through the protections attached to jobs and granted through social policies.

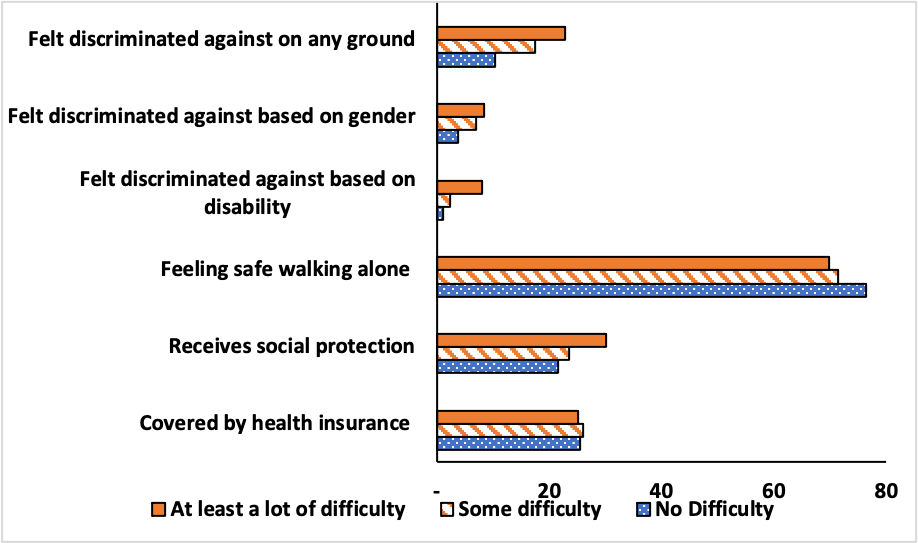

We consider six indicators related to insecurity: the share of women who 1) are covered by health insurance (SDG indicator 1.3.1/3.8.1); 2) are in households with social protection (SDG indicator 1.3.1); 3) feel safe walking alone in their neighborhood after dark (SDG indicator 16.1.4); 4) have personally felt discriminated against or harassed within the past 12 months on the basis of (a) a ground of discrimination prohibited by international human rights law19 (SDG indicator 16.b.1 & 10.3.1); (b) disability; (c) gender. The prevalence of discrimination or harassment is captured through three indicators that consider respondents’ self-reported experiences of discrimination or harassment. They rely on respondents having perceived and being aware of acts of discrimination or harassment of a direct or systemic nature as part of their personal experience (OHCHR 2021b). For (b) disability, it also relies on the persons self-identifying as having a disability which may not be the case for all persons with functional difficulties and could be the case for some persons with no reported functional difficulties. As noted earlier, the WG-SS does not capture all disabilities, but only a small set of functional domains.

The indicators on insecurity are relevant to several articles of the CRPD. In particular, under Article 5, “States Parties shall prohibit all discrimination on the basis of disability and guarantee to persons with disabilities equal and effective legal protection against discrimination on all grounds.”

A. Results

The entire set of results is available in the Insecurity Tables (2022 results table). Cross-country estimates are shown in Figure 10.1. Starting with the share of women covered by health insurance, we find no significant difference across functional difficulty status in cross-country estimates and in almost all countries. Next, we consider the share of women in households who have received social protection benefits in the past year or currently receive them (e.g. cash benefits, in kind transfers). Based on cross-country estimates, 23.5% of women with functional difficulties received social protection benefits compared to 21.5% of women with no functional difficulties. At the country level, results vary with about half of countries with similar shares across functional difficulty status and nine countries with a significantly higher share for women with functional difficulties.

Figure 10.1: Cross-country estimates for insecurity indicators among women (%)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on MICS6 data for 27 countries (discrimination), countries for walking alone, 24 countries for social protection, 26 countries for health insurance and feeling safe walking alone.

Next, we find that fewer women with functional difficulty report feeling safe walking alone in their neighborhood after dark as compared to women without functional difficulty. At the country level, the difference is statistically significant in all but one country (Zimbabwe) with a median disability gap at 6 percentage points.

Cross-country estimates suggest that persons with functional difficulties more often feel discriminated or harassed based on disability, gender, or on any ground. For the broader definition of discrimination based on any ground, 22.9%, 17.4%, and 10.4% of women with at least a lot, some, and no difficulty feel discriminated against (Table 10.1). Among subgroups of women with functional difficulties, those who live in rural areas, are between ages 18 and 29, and those with communication difficulties have a higher share of reported feeling discriminated against.

Table 10.1: Women who felt discriminated based on any ground (%)

| Sample | No Difficulty | Some difficulty | At least a lot of difficulty | Any difficulty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All women | 10.4 | 17.4 | 22.9 | 18.3 |

| Rural | 11.3 | 19.1 | 25.1 | 19.8 |

| Urban | 10.1 | 16.6 | 20.3 | 16.6 |

| Age 18-29 | 12.1 | 21.6 | 30.7 | 21.9 |

| Age 30 to 49 | 10.1 | 17.2 | 22.2 | 17.2 |

| With seeing difficulties | – | – | – | 16.8 |

| With hearing difficulties | – | – | – | 21.2 |

| With walking difficulties | – | – | – | 20.1 |

| With cognitive difficulties | – | – | – | 21.3 |

| With selfcare difficulties | – | – | – | 12.2 |

| With communication difficulties | – | – | – | 28.4 |

Source: Authors’ calculations based on MICS6 data for 26 countries (discrimination), countries for walking alone, 24 countries for social protection, 26 countries for health insurance and feeling safe walking alone.

Note: ‘-‘ refers to not applicable for ‘No difficulty’ and not available for ‘Some difficulty’ and ‘At least a lot of difficulty’ due to small sample sizes in many countries

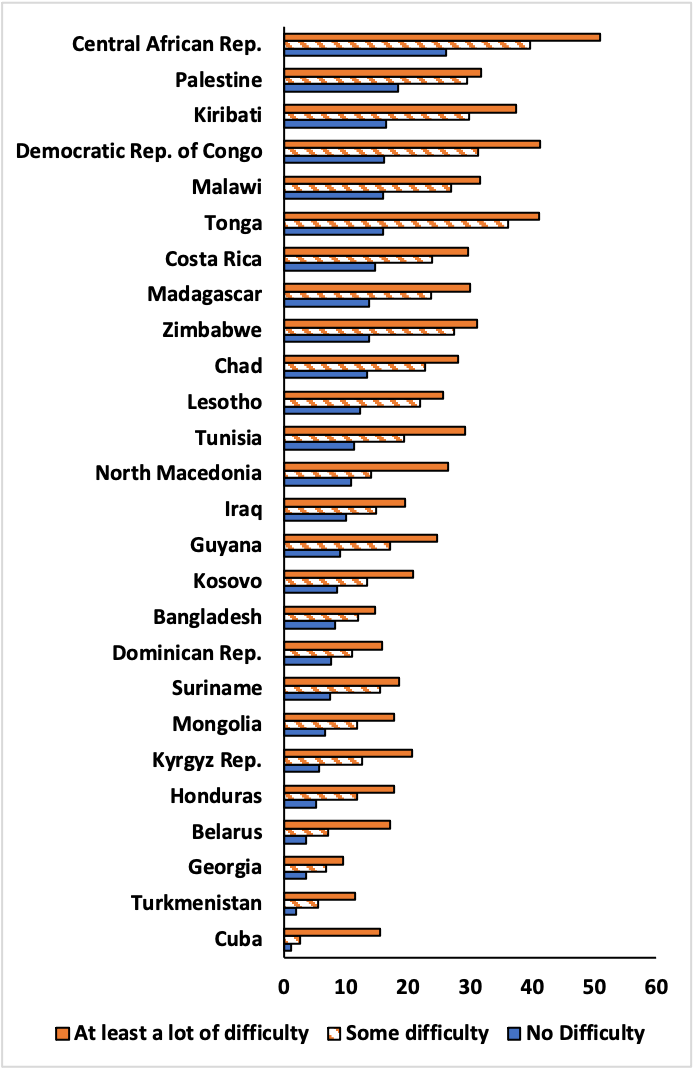

The prevalence of discrimination/harassment on any ground varies widely across countries (Figure 10.2). In all 27 countries, women with functional difficulties have a significantly larger share who have personally felt discriminated against or harassed within the past 12 months with a sizeable median disability gap of eight percentage points.

Figure 10.2: Women feeling discriminated against based on any ground (%)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on MICS6 data.

B. Discussion

The similar rates of coverage for social protection found in this Report for many countries across functional difficulty status suggest that access to social protection programs may be a concern given well established disability gaps in several economic insecurity indicators such as food insecurity and out-of-pocket medical expenses (United Nations 2019b, Mitra and Yap 2021). Access to social protection has been shown to be central to the economic wellbeing of women with disabilities (Chaudhry 2016) and restricted by a variety of barriers, including unclear eligibility criteria (Banks et al 2017). Thus, further evaluation and research to assess social protections’ accessibility and effectiveness in alleviating poverty is needed.

Relatedly, the similar rates of health insurance coverage found for women with and without functional difficulties is cause for concern as persons with disabilities have more healthcare needs but are less likely to be able to meet these needs (United Nations 2019b, WHO-World Bank 2011).

To our knowledge, this report provides new insights on the associations between functional difficulty and feeling unsafe in one’s neighborhood and feeling discriminated against or harassed. Feeling unsafe affect women in various ways, especially when fear might hinder access to essential services (Jayachandran 2015).

The data collected through MICS on discrimination gives information on the perception of discrimination or harassment. The disproportionately higher share of women with functional difficulties reporting feeling discriminated against highlights the need for efforts to understand discrimination and harassment for women with disabilities (e.g. World Bank 2020) and to examine policy responses. It reflects the importance of examining intersectionality with women with disabilities experiencing double discrimination (Habib 1995).

19 There is a list of over 20 grounds as follows: race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national origin, social origin, property, birth status, disability, age, nationality, marital and family status, sexual orientation, gender identity, health status, place of residence, economic and social situation, pregnancy, indigenous status, and other status (OHCHR 2021b). For MICS6, the most commonly asked grounds across the countries were ethnic or immigration origin, gender, sexual orientation, age, disability and others. Only the most common were used in constructing the indicator to allow for comparability across countries.

Go Back

Go Back