Multidimensional Analysis

This section describes and discusses results through a multidimensional lens whether with a multidimensional poverty measure or a dashboard, indicator by indicator, analysis. It synthesizes the deprivations or achievements considered earlier with respect to education, health, work and the standard of living and is thus relevant to several CRPD articles (24,25,27,28). It is also relevant to SDG 1 on poverty in all its forms.

Multidimensional Poverty

Background

Recently, poverty on the international scene has increasingly been understood broadly in terms of disadvantage in various dimensions of well-being (Sen 2009; UNDP 2020), as reflected in SDG 1 with poverty “in all its forms”. Poverty is multifaceted and can be measured by counting the number of deprivations experienced by an individual or household (Alkire and Foster 2011). Information on the methodology is in Appendix 3 Method brief #6. The entire set of results is available in the Multidimensional Results Tables.

Findings

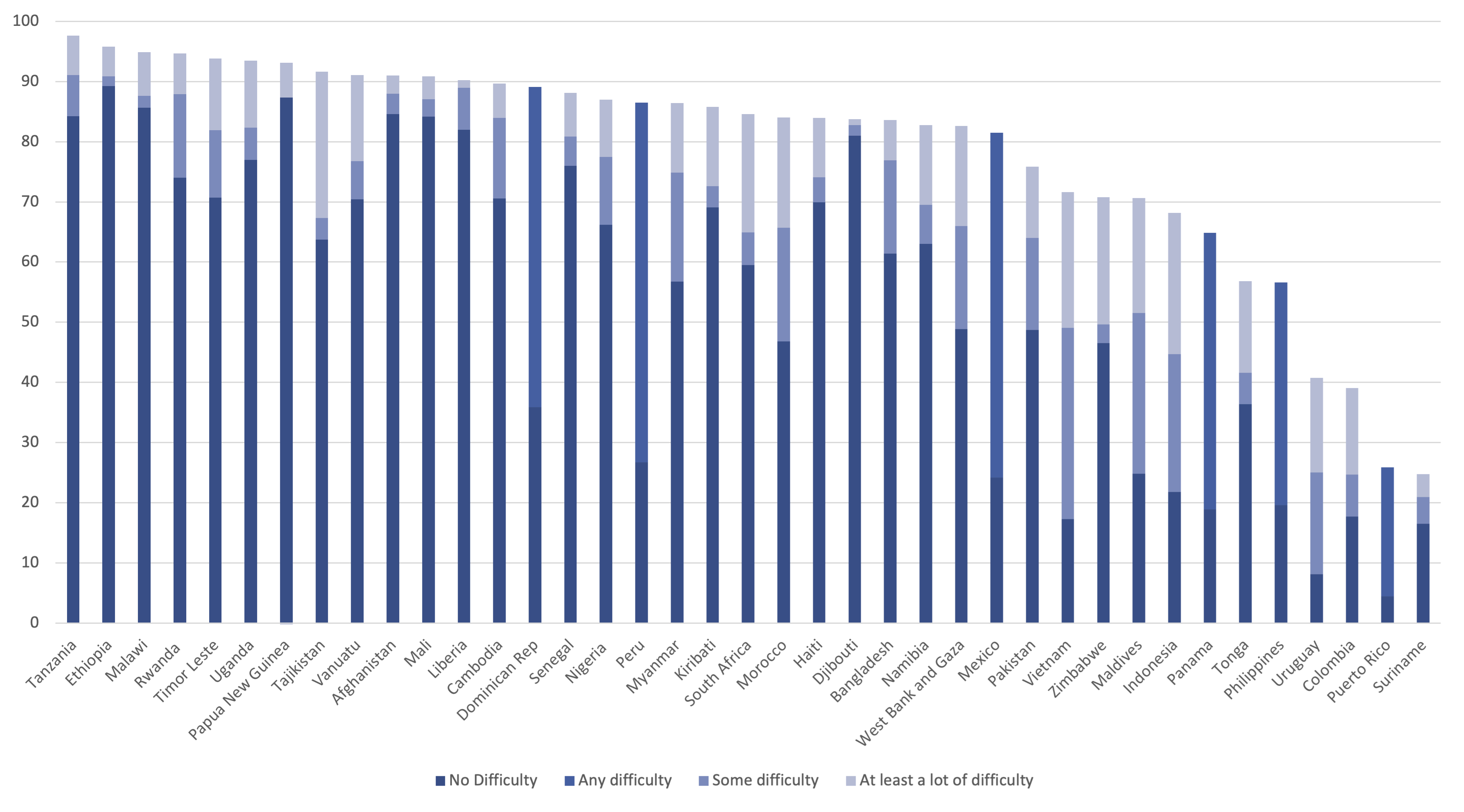

Figure 10.1 shows the headcount or the share of adults in multidimensional poverty, i.e. with more than one deprivation among four dimensions of wellbeing (education, employment, health, standard of living)[13]. In all 39 countries, persons with functional difficulties have a higher share of adults in multidimensional poverty, and the difference is statistically significant in all but one country (Djibouti). The median disability gap is sizeable at 11 percentage points based on any difficulty, and at six and 21 percentage points for some and at least a lot of difficulty respectively. This result is driven by disproportionately lower education attainment, employment-population ratios and asset ownership among persons with functional difficulties.

As shown in Figure 10.1, in terms of multidimensional poverty, persons with some functional difficulties are worse off than persons with no difficulty, but better off than persons who experience at least a lot of difficulty. At the same time, while persons with functional difficulties are disproportionately more likely to be multidimensionally poor, not all persons with functional difficulties are poor. Some persons with functional difficulties do not experience multiple deprivations.

Table 10.1 shows by type of functional difficulty the share of adults in multidimensional poverty and the indicators that underlie the multidimensional poverty measure. More precisely, it gives the median share across all countries for each type of functional difficulty. While adults with all types of functional difficulties exhibit higher headcounts than adults with no difficulty, adults with self-care and communication difficulty have higher shares in multidimensional poverty compared to persons with other types of difficulties.

Figure 10.1: Multidimensional Poverty Headcount (%)

Note: The multidimensional poverty measure is described in the report and in Method brief #6

Table 10.1: Indicator By Type of Functional Difficulty (%)

| Indicator | None | Seeing | Hearing | Mobility | Cognitive | Self-care | Communication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults who experience multidimensional poverty | 60 | 72 | 83 | 82 | 83 | 91 | 87 |

| Adults who have ever attended school | 90 | 70 | 58 | 64 | 58 | 51 | 51 |

| Adults who have completed secondary school or higher | 18 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| Adults who can read and write in any language | 68 | 46 | 38 | 39 | 34 | 25 | 32 |

| Employment population ratio | 56 | 41 | 37 | 29 | 29 | 25 | 30 |

| Adults in households using safely managed drinking water | 86 | 84 | 82 | 81 | 82 | 80 | 81 |

| Adults in households using safely managed sanitation services | 72 | 73 | 68 | 73 | 68 | 65 | 65 |

| Adults in households with adequate housing | 38 | 34 | 27 | 28 | 27 | 24 | 33 |

| Adults in households owning assets | 35 | 32 | 29 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 31 |

Source: Own calculations based on datasets in Table 4.1

Discussion

As a group, persons with disabilities, on average, experience multiple deprivations at higher rates than persons without disabilities. This result suggests that persons with disabilities should be explicitly incorporated in policymaking and research agendas related to education, health, work and the standard of living.

This consistent association between disability and multidimensional poverty comes in contrast to the relatively more mixed evidence on disability and consumption expenditures (Filmer et al 2008).

This report contributes to a growing literature that has considered the association between disability and the experience of multiple deprivations such as non-employment, low educational attainment, social isolation, poor psychological well-being. These studies, recently reviewed in United Nations (2019) have found that disability is associated with a higher likelihood of experiencing multidimensional poverty while the very nature of deprivations may vary across countries. The multidimensional poverty index (MPI) offers a measure of the experience of simultaneous deprivations at the household level and is increasingly used in international development policy and research (e.g. UNDP 2020). It has recently started to be disaggregated across disability status (Pinilla-Roncancio and Alkire 2020) but this effort is impeded by the inconsistent availability of disability data across countries in large household surveys such as the DHS or the Living Standard Measurement Study.

Multidimensional Dashboard

Multidimensional poverty considers the extent to which an adult may experience multiple deprivations. Another way to consider wellbeing or deprivations through a multidimensional lens is to consider indicators as part of a dashboard. The dashboard used in Table 10.2 includes 11 indicators that were commonly found in the 41 countries under study and include: ever attended school, educational attainment (secondary school or higher), literacy, employment population ratio, water, sanitation, electricity, clean fuel, adequate housing, asset ownership, cell phone ownership. It does not include indicators that were available for less than half of the countries (e.g. food insecurity)

Table 10.2 shows for each country, the share of indicators with a gap, which is the number of indicators with a disability gap out of the number of available indicators for that country. It ranges from a low of 50% in two countries (Afghanistan and Gambia) to a high of 100% in nine countries (Indonesia, Mauritius, Mexico, Myanmar, Namibia, Peru, Puerto Rico, Senegal, Suriname, Uruguay). The median is at 80%. These results suggest that for the indicators covered in this study and covering education, work, health and the standard of living, inequalities are commonly found and for some countries are consistent across indicators.

Table 10.2: Share of Indicators With a Disability Gap in Each Country

| Country | Share of indicators |

|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 5/10 |

| Bangladesh | 7/10 |

| Cambodia | 8/10 |

| Colombia | 5/11 |

| Djibouti | 6/11 |

| Dominican Rep | 6/11 |

| Ethiopia | 8/11 |

| Gambia | 2/4 |

| Haiti | 8/10 |

| Indonesia | 11/11 |

| Kiribati | 10/10 |

| Liberia | 10/11 |

| Malawi | 7/11 |

| Maldives | 8/10 |

| Mali | 8/10 |

| Mauritius | 4/4 |

| Mexico | 11/11 |

| Morocco | 10/11 |

| Myanmar | 11/11 |

| Namibia | 11/11 |

| Nigeria | 8/11 |

| Pakistan | 7/10 |

| Panama | 10/11 |

| Papua New Guinea | 9/11 |

| Peru | 11/11 |

| Philippines | 8/10 |

| Puerto Rico | 3/3 |

| Rwanda | 8/10 |

| Senegal | 11/11 |

| South Africa | 6/11 |

| Suriname | 10/10 |

| Tajikistan | 5/9 |

| Tanzania | 8/11 |

| Timor Leste | 9/10 |

| Tonga | 6/11 |

| Uganda | 10/11 |

| Uruguay | 10/10 |

| Vanuatu | 9/11 |

| Vietnam | 10/11 |

| West Bank and Gaza | 7/11 |

| Zimbabwe | 8/9 |

Source: Own calculations based on datasets in Table 4.1.

[13] Details on the indicators and thresholds are in Appendix 3 Method brief #4.

Go Back

Go Back