Personal Activities

The activities people have matter for their wellbeing. Stiglitz et al. (2009) put forward a wide range of personal activities to be considered to assess wellbeing, in particular paid work, unpaid work, commuting, and leisure time. MICS6 does not have information on such activities but has information on access to information and communication technologies (ICT) which are determinants of how people spend their time and the activities they have. They are also determinants of their autonomy. SDG 9C aims at significantly increasing access to information and communications technology and providing universal and affordable access to the internet in low-income countries by 2020. The shorter timeline compared to other goals in the 2030 Agenda highlights the significant role of ICT in achieving the other SDGs.

In addition, mobile phone ownership is important for gender equality since a mobile phone is a personal device that, if owned and not just shared, may provide women with a degree of independence and autonomy, including for work. Several studies have highlighted the link between mobile phone ownership and empowerment, and productivity growth (Hossain and Samad 2021).

Article 21 of the CRPD has the goal to ensure that persons with disabilities can exercise the right to freedom of expression and opinion, including the freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas on an equal basis with others. In addition, to achieve the goal to “enable persons with disabilities to live independently and participate fully in all aspects of life,” Article 9 provides that States Parties take appropriate measures to ensure that persons with disabilities have access to a wide of range of services, including ICT and systems, including internet service. Therefore, information and ICT need to be accessible as well as affordable to persons with disabilities.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, access to crucial information became more challenging as people were more isolated. ICT became a way to access information – information such as the constantly updating COVID-19 restrictions, health and safety campaigns, and access to essential healthcare services such as telemedicine. ICT became highly integrated with daily life – in schools and in many workplaces as classes were taught remotely and meetings and communications among workers were conducted online. With restrictions imposed on physical social gatherings, ICT became a way to remain in touch with relatives and friends.

For our analysis, we use four MICS indicators available in 28 countries on access to information and ICT to explore disability gaps among women . These are the shares of women who 1) read a newspaper or magazine, listen to the radio, or watch television at least once a week; 2) used the internet in the past three months; 3) used a computer in the past three months; and 4) own a mobile phone (SDG indicator 5.b.1.).

A. Results

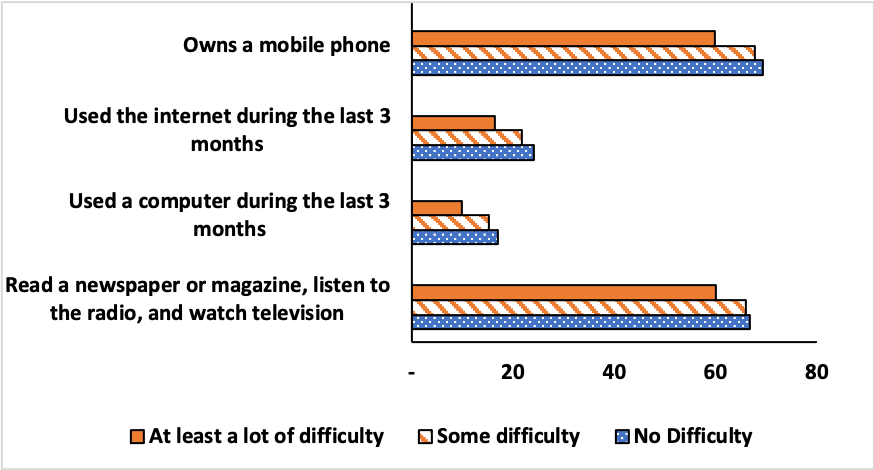

The entire set of results is available in the Personal Activities Tables 2022 results table. In most countries and in cross-country estimates, results point at women with at least a lot of functional difficulties being worse off. Cross-country estimates are shown in Figure 6.1. For all four indicators, cross-country estimates point towards a disability gap for women with at least a lot of difficulties. For women with some difficulties the gap is small and not statistically significant. For instance, rates of mobile phone ownership stand at 69%, 68% and 60% among women with no, some, and at least a lot of difficulty respectively.

Figure 6.1: Cross-country estimates for personal activities among women (%)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on MICS6 data for 27 countries

Table 6.1 zooms into the cross-country estimates for the share of women owning a mobile phone, showing younger women and women in rural areas less often owning cellphones. Women with self-care difficulties have the lowest rates of cellphone ownership.

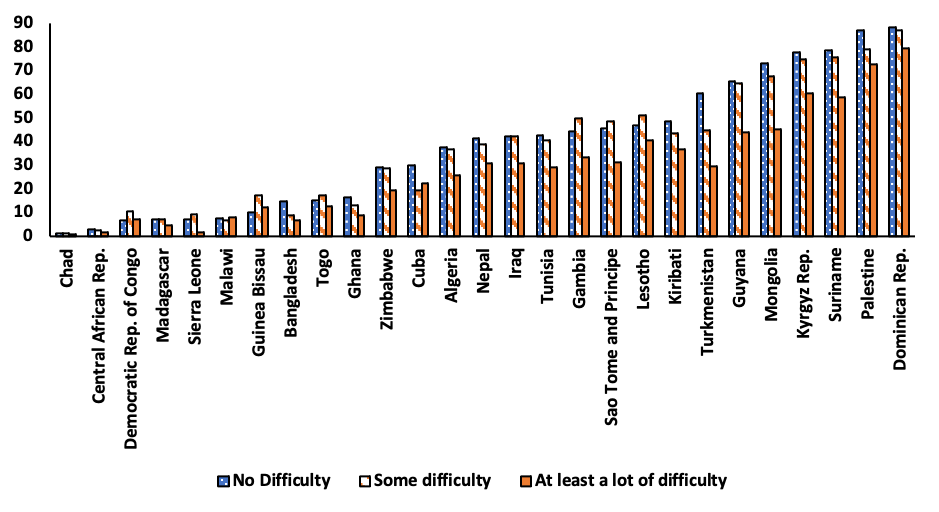

At the country level, there is a disability gap in the three ICT indicators for most of the countries. This is illustrated in Figure 6.2 for internet use.

Overall, there are two main findings regarding ICT usage. First, when rates of computer, internet, or mobile phone access are low such as in Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, Guinea Bissau, and Togo, there is no disability gap. Second, among countries with higher ICT access rates, there is a gradient for some countries. For example, for computer usage, in 16 out of 28 countries, women with some difficulties are worse off than women with no difficulty but better off than women with at least a lot of difficulty. The case of Bangladesh is an illustration of this gradient with mobile phone ownership at 63%, 72%, and 77% for women with at least a lot of difficult, some difficulty, and no difficulty.

For the share of women who read a newspaper or magazine, listen to the radio, or watch television at least once a week, the disability gap is present in 14 countries for those with at least a lot of difficulties11. The median value of this gap is seven percentage point.

Table 6.1: Cross-country estimates for mobile phone ownership among women (%)

| Sample | No Difficulty | Some difficulty | At least a lot of difficulty | Any difficulty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All women | 69.4 | 67.7 | 59.9 | 66.6 |

| Rural | 58.7 | 56.0 | 48.6 | 55.2 |

| Urban | 81.6 | 80.4 | 75.0 | 80.0 |

| Age 18 to 29 | 66.6 | 67.3 | 56.4 | 66.5 |

| Age 30 to 49 | 71.0 | 68.8 | 62.5 | 68.1 |

| With seeing difficulties | – | – | – | 68.2 |

| With hearing difficulties | – | – | – | 58.6 |

| With walking difficulties | – | – | – | 65.9 |

| With cognitive difficulties | – | – | – | 63.9 |

| With selfcare difficulties | – | – | – | 55.8 |

| With communication difficulties | – | – | – | 58.8 |

Source: Authors’ calculations based on MICS6 data for 27 countries

Note: ‘-‘ refers to not applicable for ‘No difficulty’ and not available for ‘Some difficulty’ and ‘At least a lot of difficulty’ due to small sample sizes in many countries

Figure 6.2: Internet use among women (%)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on MICS6 data

B. Discussion

Results on activities related to ICT demonstrate a digital divide between women with and without functional difficulties in most countries as reflected in disability gaps in computer use, internet use and mobile phone ownership. This digital divide may be due to a variety of reasons. For example, many persons with functional difficulties have lower educational attainment in terms of rates of secondary school completion or higher have significantly lower rates of ICT usage. Other reasons may be that women with functional difficulties may not be able to afford a computer and internet access or have limited access to ICT in their households. This may explain to some extent the disability gaps in computer use, internet use and mobile phone ownership.

A recent study found that in most countries in the global south, the gender gap in smart phone ownership has reduced (GSMA 2021). The accessibility of internet in terms of availability and affordability of internet varies considerably across countries and within countries. Several studies find that women in the global south are significantly less likely to use the Internet than men (e.g., Antonio and Tuffley 2014). In this context, the disability gap we find for ICT indicators in many countries points towards the dual penalty stemming from the intersection of gender and disability in many countries which warrants further research and policy attention.

11 These countries are: Algeria, Bangladesh, Chad, Gambia, Ghana, Kyrgyz Rep., Madagascar, Mongolia, Nepal, Sierra Leone, Suriname, Tunisia, Turkmenistan, Zimbabwe.

Go Back

Go Back